This article is a summary analysis of the book Vodka Politics by Mark Lawrence Schrad by Mark Lawrence Shrad, professor of political science at Villanova University.

Schrad wrote this book with the goal of addressing how Russian diplomacy often includes the deployment of a large amount of alcohol, particularly as his title implies, vodka. He explores vodka’s evolution under the czars and how it was employed by the soviets to control their internal enemies and allies alike. It is a problematic tradition that continues to this day, according Schrad’s thesis:

“Putin and every Russian autocrat who follows will continue the eternal battle with corruption. Whether genuine or halfhearted, every such attempt is likewise doomed to fail until they meaning-fully confront the nexus of alcohol, corruption, and autocracy that constitutes Russian vodka politics”

Vodka Politics, p.100

Schrad makes a strong argument that the use of alcohol (primarily vodka and wine) played an integral role within Russian politics and that it remains pervasive through to our present time. The author, however, does not address the fact the employment of alcohol as a tool within diplomatic negotiations or a business deal is not a uniquely Russian trait. He also argues on the premise that vodka is used as an implement tied to corruption and intimidation, but he does not acknowledge how it can also be an ice breaker or a divining tool. What else were balls or state dinners, if not parties used to loosen up allies and enemies alike to prepare for back-room meetings to discuss matters of state and business abroad?

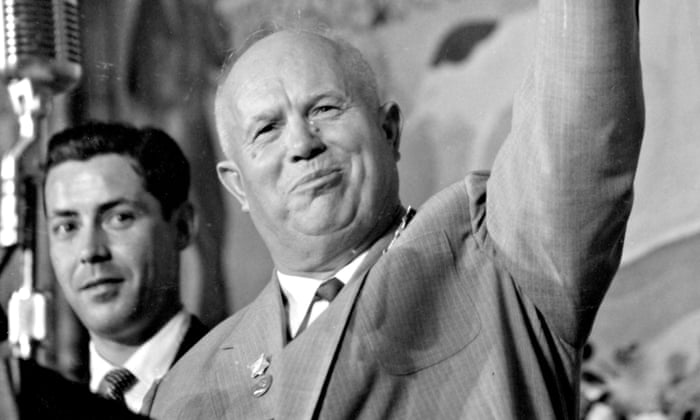

To illustrate the prevalence of vodka’s use and abuse to even the highest level of government the book’s introduction discusses Stalin and how he used alcohol to dominate his inner circle. During his spare time at his private residence Stalin would subject his close henchmen such as his secret police chief Beria, foreign minister Molotov, and especially future party leader Nikita Khrushchev to vodka-fueled drunken brawls as part of his personal entertainment or sport (p. 6). This caused Khrushchev a lot of grief and trauma which continued to torment him personally when he became the next soviet premier (p. 9).

Stalin used a variety of alcoholic drinks to both subdue his inner circle and intimidate foreign delegates. One example mentioned was a meeting with Stalin and a prominent Nazi official foreign minister, Joachim von Ribbentrop. Before hostilities escalated between Germany and Russia, Ribbentrop was sent to negotiate a nonaggression pact in 1939. During one of the celebrations Ribbentrop was amazed at the impact of drinking a cup of brown pepper vodka. The drink left him almost incapacitated while Stalin remained calm and collective. It was later revealed that Stalin intentionally drank Crimean wine that was the same color as the much stronger vodka (p. 4). The switch allowed Stalin to maintain his soberness, there by defining who was really in charge. There is a clear irony that one of Russia’s most powerful rulers would refer to vodka as “devilish” knowing that this drink pulls tricks, which was likely one of the reasons why Stalin would avoid it, sipping wine instead.

One significant contribution of this book is the revelation that the methods of conducting politics with vodka’s assistance goes way back to the first czar. Like Stalin, Ivan the Terrible also used alcohol to divide and control his supposed enemies. Ivan would also encourage his nobles, known as boyars, to partake in drunken festivities. The boyars that chose not to partake in were put on watch or publicly denounced by the czar. One difference however the author noted is that while Stalin quietly abstained from drinking alcohol to keep a calm façade offering just a glaring toast to keep his henchmen in line, leaving them to conduct the retribution of dissenting boyars or do the torture of his enemies. Ivan, on the other hand, actively participated in not just drinking but, punishing the boyars who disobeyed him. When one boyar named Mochan Mitkov called Ivan the “dammed”, Ivan got his sharpened staff and personally impaled him (p.31).

Another element this book delved into was why do Russians make vodka their favorite choice compared to other drinks? The book references an unofficial study called “geoalcoholics” that relates certain types of drinks with the geography and climate that created them. This has created something of a “drinking culture” in each region. Grapes grow in warm weather and so the southwest Europe drink wine. Beer, a product of wheat and barley crops is historically the choice for Germany and Britain (p.76). Vodka can made from a variety crops that grow in the northern climates such as corn, wheat, rye and even potatoes. Therefore, not just Russia, but most of eastern europe developed a taste for vodka simply because it could be made from food sources readily available to them.

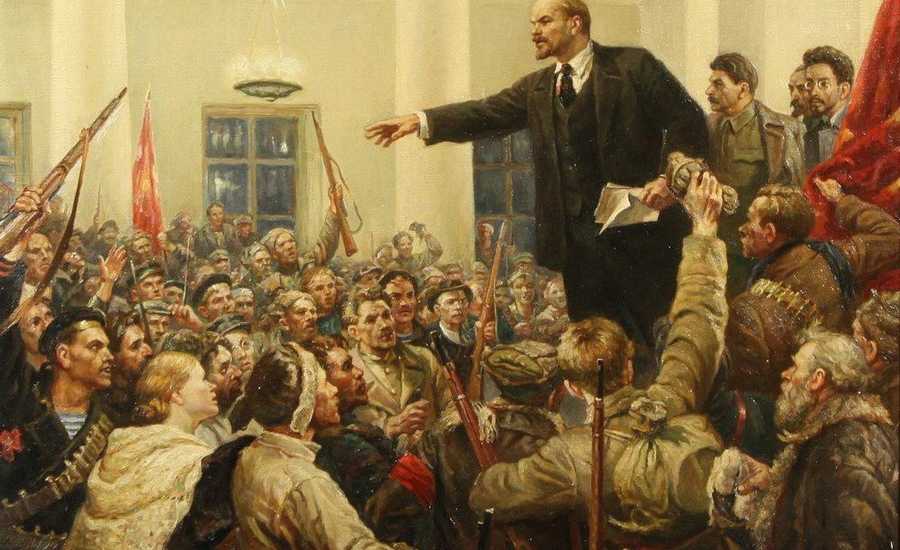

Given the prominence of vodka in everyday Russian life and its perceived detriment to society there were attempts made to reform or abolish its consumption. At the start of World War I, the last czar Nicholas the 2nd decreed that Russia would be “dry” (p.185). Since Nicholas believed in the romanticized notion of honor and discipline among the Russian army, was convinced that the consumption would hinder the war effort. This policy resulted in consequences which lead to one intriguing question asked in the book: did probation cause the revolution?

There were tensions among the czar’s gentry as some of them such as Pyotr Bukov monopolized alcoholic beverage sales, earning them a fortune (p.185). Schrad seems to be suggesting that prohibition made people more aware of their countries state though his selected quote: “Our sobriety was forced upon us, and at a time when every good person, even without probation, cannot enjoy life” (p. 190). It’s clear that alcohol has been so part of Russian society from top to bottom that this is a drinking culture that cannot be shaken off, no matter who is in charge. Despite all the hopes of a revolution, they were not able to extinguish corruption within the new autocracy that rose within the communist party under the control of Stalin.

This ultimately leads back to the question asked before: Is this practice of combining alcohol with attempts to gain power and influence unique to Russia? Based on the history and evidence, author Mark Schrad wrote in this book I do agree that the consumption of Vodka has play a significant impact on Russian Politics. Where I disagree is that the use of alcohol in diplomacy is a uniquely Russian trait as the author implies. The practice of incorporating alcohol in business negotiations is a common practice in Asia. My father worked for many years completing business deals with Chinese, Japanese and Korean, meeting with colleagues, clients and suppliers. Many business deals are worked out at the end of the day meetings over a glass of wine, scotch or bijou. Just as in Russia, alcoholic beverages drinks are often used as a means to expose a person’s true intentions and to see if they can be trusted.

The concept that alcohol is always linked to corruption could also be challenged. In eastern asian cultures, it is not unusual to take out prospective employees or business acquisitions for an evening of dining and drinking of as a means of finding out what they really think and who they really are. Alcohol lowers people’s inhibitions, enabling unguarded conversation, which can sometimes clarify things, or complicate them. This was the advantage the that Russian leaders may have used to exploit their opponents, but likewise could have helped them discover the true loyalties and views of their colleagues and allies. As in the past, alcohol in various forms sometimes acts as a divining tool, to seek the truth, and not necessarily to corrupt or intimidate.

. Russia’s history has been defined by great power and great loss. Through wars and diplomacy, what is often overlooked was the effects of vodka in Russian society. The vodka reach is from top to bottom, raised in glasses by the peasants using it to compensate for a harsh life, or offered as a toast by an autocrat manipulating his supposed enemies. Vodka was judiciously served by Ivan, all the way to Putin. For better, worse, or just plain life itself, Vodka is here to stay and will be playing its role in years to come.